Table of Contents

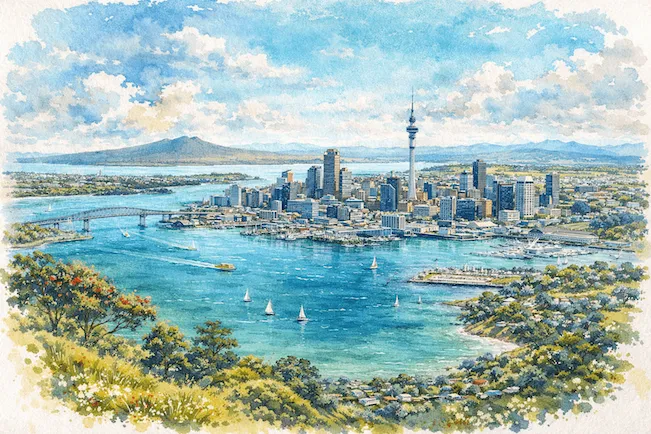

Securitisation in New Zealand has evolved quietly but steadily into a reliable component of the country’s financial system. Rather than being driven by a single, codified securitisation statute, the market has developed through the disciplined application of existing trust, property, consumer credit, tax, and financial markets law. The result is a framework that is conservative in tone, highly functional in practice, and well suited to both domestic funding programmes and cross-border transactions.

At its core, the New Zealand securitisation market reflects the country’s broader legal philosophy: substance matters more than form, and legal certainty is achieved through clarity of structure rather than regulatory prescription. Residential mortgages dominate issuance, but the framework is flexible enough to accommodate auto loans, equipment leases, personal loans, and credit card receivables. There are no categories of assets that are prohibited from being securitised as a matter of law. Instead, market discipline determines what works. Assets that lack sufficient scale, performance history, or data integrity tend simply not to be securitised.

What distinguishes New Zealand from many other jurisdictions is the absence of a dedicated securitisation regime. There is no single statute that defines what a securitisation is or how it must be conducted. Instead, securitisations are built from the ground up using general legal principles. Trust law provides the backbone of the structure, financial markets legislation governs the issuance of securities, consumer protection statutes safeguard borrowers, and property and insolvency laws determine how assets are transferred, perfected, and protected if something goes wrong.

The most common structure is a bankruptcy-remote trust. In a typical transaction, an originator sells a pool of receivables to a special purpose trust. That trust, acting through a professional trustee, issues debt securities to wholesale investors and uses the proceeds to fund the purchase of the assets. The trustee holds legal title to the receivables, while a separate security trustee holds security over the trust assets for the benefit of noteholders. Day-to-day administration is usually delegated back to the originator or an affiliated servicer, preserving operational continuity and borrower relationships.

This trust-based model is not accidental. Under New Zealand law, trusts are legally distinct from their settlors and beneficiaries. When properly structured, they provide a high degree of insulation from the insolvency risk of the originator. Courts will respect this separation provided the transfer of assets is a genuine sale rather than a disguised secured loan. In assessing whether a true sale has occurred, New Zealand courts look beyond labels to the economic substance of the transaction. If the originator has truly relinquished control and economic benefit, the assets will sit outside the originator’s insolvency estate.

The regulatory environment surrounding these structures is deliberately fragmented. There is no single securitisation regulator. Instead, oversight is shared among several agencies depending on the nature of the participants and the assets involved. Financial markets conduct and licensing issues fall under the supervision of the Financial Markets Authority. Consumer credit issues are overseen through the consumer finance regime, with enforcement responsibilities transitioning toward the same authority. Prudential regulation applies where banks or deposit takers are involved, while anti-money laundering obligations and privacy protections apply across the board. Taxation, as always, sits with the Inland Revenue Department.

This multi-agency approach can appear complex, but it offers flexibility. Most securitisations are private transactions offered exclusively to wholesale investors, which significantly reduces disclosure burdens and regulatory friction. New Zealand does not operate a public securitisation regime comparable to those in Europe or the United States. There are no retail prospectuses, no public transaction repositories, and no formal “simple, transparent and comparable” designation. Instead, market confidence is driven by conservative asset selection, robust documentation, and the reputation of issuers and arrangers.

From an operational perspective, perfection of interests is critical. New Zealand’s personal property securities regime treats the sale of receivables as giving rise to a deemed security interest. As a result, even where a transaction is structured as an outright sale, registration on the personal property securities register is essential to establish priority against competing creditors. In practice, this registration functions as a form of public notice, reducing the need for immediate borrower notification. In consumer transactions, specific exemptions allow originators to continue servicing loans without disrupting borrower relationships, provided certain conditions are met.

Tax treatment is another area where New Zealand’s framework is notably facilitative. Securitisation vehicles are generally designed to be tax neutral. This can be achieved either through a flow-through regime for qualifying debt funding vehicles or through the use of a complying trust, where income is automatically attributed to the beneficiary. Withholding tax considerations are carefully managed, particularly in transactions involving offshore investors, but the overall system is designed to avoid tax leakage at the vehicle level.

Data protection and confidentiality obligations are taken seriously. Borrower information can be transferred and used for securitisation purposes, but only within the boundaries set by privacy law. Originators must be transparent about how personal information may be shared, and robust safeguards are required to prevent misuse or unauthorised disclosure. These requirements have become increasingly important as data quality and analytics play a larger role in investor due diligence.

New Zealand’s legal framework is also broadly accommodating of cross-border securitisations. There are no structural barriers to offshore issuance or foreign investment, although transactions involving land or large asset values can trigger overseas investment consent requirements. In practice, most securitisations benefit from exemptions designed specifically to avoid capturing routine financing arrangements.

Looking ahead, there is little indication that New Zealand intends to introduce a bespoke securitisation statute. Incremental reforms continue in adjacent areas, particularly consumer credit and regulatory supervision, but the underlying architecture remains stable. For issuers and investors alike, this stability is one of the jurisdiction’s key attractions.

In narrative terms, New Zealand’s securitisation framework can be understood as quietly effective rather than overtly engineered. It relies on well-understood legal principles, disciplined structuring, and a strong culture of compliance. For participants willing to engage with its trust-centric, substance-driven approach, it offers a legally robust and commercially practical environment for structured finance transactions.

1. Market Activity and Asset Classes

New Zealand’s securitisation market is well-established and conservative in character. Issuance volumes over the past decade reflect consistent use of securitisation as a funding and risk-management tool rather than episodic market activity.

Commonly securitised assets include:

- Residential mortgage loans (the dominant asset class)

- Motor vehicle and auto loans

- Equipment and operating leases

- Personal and consumer loans

- Credit card receivables

There are no statutory prohibitions on the types of assets that may be securitised. Practical constraints—such as asset homogeneity, performance history, data quality, and scale—are the main determinants of securitisability.

2. Absence of a Single Securitisation Statute

Unlike jurisdictions with codified securitisation regimes, New Zealand regulates securitisations through existing general legislation, applied functionally to structured finance transactions.

Key legislative pillars include:

Trust and Structural Law

- Trusts Act 2019 – governing trusts, trustees, fiduciary duties, and asset holding arrangements used in securitisation SPVs.

Financial Markets and Conduct

- Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013 (FMCA) – governing the offer and issuance of financial products, disclosure, fair dealing, and wholesale investor participation.

- Financial Service Providers (Registration and Dispute Resolution) Act 2008 – requiring certain transaction participants to register as financial service providers.

Consumer Protection

- Credit Contracts and Consumer Finance Act 2003 (CCCFA) – applicable where securitised receivables arise from consumer credit contracts (e.g. mortgages, personal loans, credit cards).

- Fair Trading Act 1986 – prohibiting misleading or deceptive conduct and regulating unfair contract terms.

Operational and Compliance Regimes

- Anti-Money Laundering and Countering Financing of Terrorism Act 2009

- Privacy Act 2020 – governing borrower data and personal information used in securitisations.

Property, Security, and Insolvency

- Personal Property Securities Act 1999 (PPSA)

- Property Law Act 2007

- Companies Act 1993 (insolvency clawback and voidable transaction rules)

Taxation

- Income Tax Act 2007

- Goods and Services Tax Act 1985

- Tax Administration Act 1994

3. Typical Securitisation Structures

SPV Form

Most New Zealand securitisations use a bankruptcy-remote trust SPV, although limited partnerships and companies are legally permissible in limited cases.

Core Transaction Parties

- Originator / Sponsor – originates and sells the receivables

- Issuer Trustee – holds legal title to assets and issues notes

- Security Trustee – holds security on behalf of noteholders

- Trust Manager – oversees day-to-day trust administration

- Servicer – manages receivables, collections, and borrower interface

- Investors – typically wholesale investors only

Tax-Driven Design

Trusts are deliberately structured to avoid being treated as “unit trusts,” which would otherwise be taxed as companies. Most vehicles have a single beneficiary to preserve tax neutrality.

4. Regulatory Oversight: A Multi-Agency Model

There is no single securitisation regulator in New Zealand. Oversight depends on transaction features and participant roles:

- Financial Markets Authority (FMA) – financial markets conduct, securities issuance, licensing

- Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) – prudential regulation of registered banks and deposit takers

- Commerce Commission – consumer credit and fair trading enforcement (with functions transitioning to the FMA)

- Department of Internal Affairs (DIA) – AML/CFT supervision

- Office of the Privacy Commissioner – data protection

- Inland Revenue Department (IRD) – taxation

This distributed model offers flexibility but requires careful regulatory mapping during transaction structuring.

5. Investor Access and Transaction Type

All securitisations in New Zealand are private, wholesale transactions. There is no public securitisation regime involving retail prospectuses or public repositories.

Participation is limited to:

- Wholesale investors under the FMCA

- Offshore investors subject to equivalent foreign regimes

6. Registration, Filings, and Perfection

Personal Property Securities Register (PPSR)

Under the PPSA:

- Transfers of receivables create deemed security interests

- These must be perfected by registering financing statements on the PPSR

- Priority is determined by time of registration

Failure to register does not invalidate the assignment but can defeat priority in insolvency.

Property and Mortgage Registration

- Transfers of mortgages require registration with Land Information New Zealand

- Assignments of receivables may rely on delayed notification and title-perfection triggers

Consumer Credit Disclosure

Where CCCFA applies:

- Borrowers must generally be notified of receivable transfers

- Specific securitisation exemptions allow servicing to remain with the originator without immediate borrower notification

7. True Sale and Bankruptcy Remoteness

Achieving a True Sale

Courts assess:

- Substance over form

- Transfer of economic risk and benefit

- Absence of seller control or re-purchase obligations

Transactions that resemble secured lending may be recharacterised.

Bankruptcy Remoteness

SPVs achieve isolation through:

- Trust structures

- Non-petition and limited-recourse covenants

- True sale asset transfers

- Independent trusteeship

8. Credit Enhancement Techniques

Common enhancements include:

- Subordinated note tranches

- Over-collateralisation

- Cash reserve accounts

Although New Zealand law does not mandate risk retention, sponsors typically retain junior tranches as a market convention and to satisfy offshore regulatory expectations.

9. Tax Treatment and Neutrality

Two Principal Tax Paths

- Flow-Through Regime for Debt Funding SPVs

- SPV treated as tax-transparent

- Originator taxed directly

- Complying Trust Treatment

- Income automatically vests in beneficiary

- Trustee files nominal or nil returns

Withholding Tax

- Domestic withholding applies to resident investors

- Non-resident withholding may be replaced with a 2% approved issuer levy

10. Data Protection and Borrower Confidentiality

The Privacy Act imposes:

- Purpose-limitation on data use

- Disclosure obligations via privacy policies

- Security safeguards

- Mandatory breach notifications for serious harm events

Originators must disclose that borrower information may be transferred to securitisation vehicles and assignees.

11. Cross-Border and Offshore Transactions

New Zealand law is broadly permissive of cross-border securitisations, subject to:

- AML/CFT restrictions

- Overseas Investment Act consent requirements (with broad securitisation exemptions)

- Tax residency limitations for flow-through SPVs

12. Enforcement, Liability, and Penalties

Breaches may result in:

- Civil penalties under the FMCA

- Consumer redress under the CCCFA

- Significant fines for overseas investment breaches

- Tax penalties and interest

- Prudential sanctions for regulated banks

13. Future Direction of the Framework

While no dedicated securitisation statute is expected, ongoing reforms are reshaping the environment:

- Simplification of consumer credit regulation

- Consolidation of AML/CFT supervision

- Incremental improvements to tax clarity

New Zealand’s framework remains principles-based, flexible, and market-friendly, making it particularly attractive for high-quality, vanilla securitisations and cross-border funding structures.

Key Takeaway

New Zealand offers a robust, low-friction securitisation environment built on trust law, tax neutrality, and strong creditor protections—without the rigidity of a single, prescriptive securitisation code. Its framework rewards careful structuring and disciplined execution, making it especially suitable for institutional issuers and investors seeking stability and legal certainty.